Race, Art, and All That Jazz at Harvard

jeffrey mcnary | 26.03.2016 12:53 | Anti-racism | Culture

Comes now, The Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at Harvard University with it's remarkable exhibition fusing music to the visual. In,“Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes,” the viewer finds a history laced exhibition summoning, teaching, delighting and informing. It’s another outright eschatological festival for the Gallery. It matches, if not surpases, previous exhibitions, including its coming on the scene, “Luminos/C/ity.Ordinary Joy” in autumn of 2014, followed by, “Drapetomania: Grupo Antillano and the Art of Afro-Cuba”, and later the acclaimed, “Black Chronicles II”. This current three-part exhibition rhythmically lays down, elevates, and takes “giant steps”.

The show is complex, far from the norm, making a reach toward two on campus locales with varying visions of its dynamic. With more than 70 pieces ranging from early jazz age objects to mid-century jazz ephemera to contemporary works by established African American artists, the exhibition explores, Janus like, the beginnings of jazz and traces how it was, and is embraced internationally as an art form, a social movement and its musical iconography for Black expression. Held in conjunction with the Harvard Art Museum, private collectors, the Studio Museum in Harlem, DC Moore Gallery and Luhring Augustine Gallery with a bold, and challenging exploration of the interaction of history, music, and the visual providing a full, many sided exhibition.

Form, and Performance, curated by Harvard University art historians Suzanne Blier, Allen Whitehill Clowes Chair of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies, and David Bindman, Emerititus Professor of the History of Art at University College, and current Dubois Fellow at Harvard, is primarily a collection of works stemming from a course they taught. “The selection of objects was dictated by what is available in the Harvard collections with some loans”, shared Bindman, "..it is mainly a student led exhibition." Notes, the third part is curated by Vera Ingrid Grant, Director of the Cooper Gallery, and illustrates 20th and 21st century, a time when many began and continue to develop personal styles.

“We wanted the three components in the ‘Art of Jazz’ exhibition to reflect the idea of call-and-response’", shared Grant in a media release, "the spontaneous interaction between musicians that’s a basic of jazz music. Notes", she continues, "is the response to the call of Performance and Form".

Entering the Gallery, the visitor is greeted by Cullen Washington’s, Space Time, 2012 Mixed Media, 10’x9’, filled with tension, with grid and challenged structure. It’s a jolting intro to much of “4th beat”, the rhythmic organization prevalent in some jazz. . Four-beat was especially common during the swing era and afterwards, but is found in earlier jazz.It'sdisrupting, in sound and in imagination. It’s re-defining, and tension building.

Along an adjoining 'ramp gallery' leading to more space, one finds assorted albumn covers mounted, providing a sound installation and a stroll back in time. There's a Warhol, Count Basie and his Orchestra, Count Basie, 1955, Album Cover; Jackson Pollock's, The Ornette Coleman Double Quartet, Free Jazz, with Pollock Painting Cover, 1961, Album Cover, 12" x 12"; Romare Bearden, Thank you for Funking Up My Life, Donald Byrd, 1978, Album, 12" x 12", and more, crowned by hanging sound cones providing a sound component, a sampling of the album for the viewer.

Bearden's work is prevelant in the show. A member of the Harlem Artists Guild, Bearden was inspired by the work of Picasso and Matisse (also represented in the Form segment) as well as African Art . This African-American artist's collages along with his water colors, reflect his interests in both musical and literary arenas, with still other album covers including, J Mood, Wynton Marsalis, 1986; 12" x 12", as well as Bradford Marsalis', Reproducing Bearden's Profile Part II, The Thirties' Artist with Painting and Model, 2003, Album, 5" 1/2 x4 9/10".Also present are his, Grandma and Granddaughter, 1985, Collage and Watercolor, 12 x 9"; along with Conjunction, 1212, Color Lithogrph, 18 5/8 x 143/4". Much of this work is on loan from Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, a Bearden partisan who previously spoke of the painter’s, "mastery" of collage.

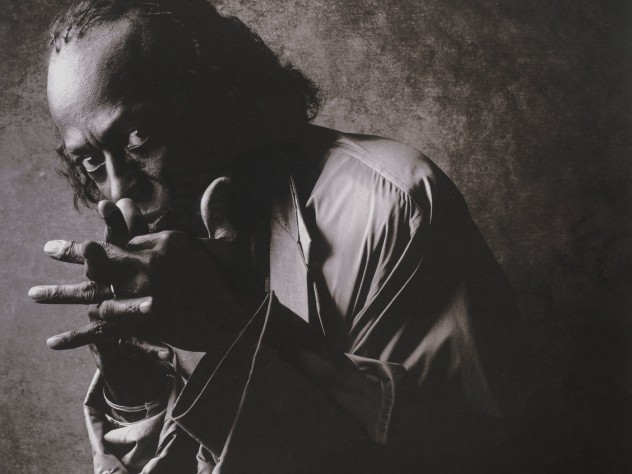

Carving a place into the show is, Harlem Renaissance painter, Beauford Delaney. A friend of Henry Miller, he'd done pastels of Ellington and W.E.B. Dubois, and his stunning, My Friend James Baldwin, 1966, Oil on Canvas, 45 7/8" x 35" conjures Baldwin's work, "Sonny's Blues". That writing had been cited as, "the most famous jazz short story ever written", in the introduction to, "The Jazz Fiction Anthology”. It's at home here, promising more just ahead.. And just ahead is William Coupon's, Miles Davis, 1986, Archival Digital Print (monochrome, sepia toned) 14" x 14". Miles, prince of darkness, king of the fuck-it-all cool leans forward and glares. It's a picture essay.

Photography has, at times, tangled with other forms of media, yet here, it's not the case.The educational, historical value of photography fits well with the works mounted in the exhibition and the stories they tell. There is little attempt at voguing.

Of one Hugh Cecil Lancelot Bell, best known for his jazz photographs from the 1950s and 1960s. Prof. Bindman shares, "..the photos of Hugh Bell are a real discovery. He is little known but a brilliant photographer who captured many musicians of the Bebop era." In fact, he photographed fashion and still life images for Esquire, Ebony, Essence, and other outlets, as well as engaging in Steichen's, historic, "The Family of Man".

We catch Parker’s cool energy here in Bell’s, Charlie Parker and Treddie Kotick at Open Door Café, 1953, Gelatin Silver Print, 8”x10”. There is a pained series, Billie Holiday, Carnegie Hall Dressing Room, 1957. Of the four, two are 11" x 14", one 8" x 10" and another 16" x 20", all Black and White and all catching Lady Day appearing cornered… upon and afraid…

Social observers note the genre’s evolution in a host of writings. “For black Americans”, writes Brian Priestley in his biography of Charles Mingus simply titled, Mingus, “the hopes and fears of that decade of indecision, 1945-55 were expressed in markedly different ways. The two archetypes of their generation, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, reflected a deep polarization of attitudes: the alienated yet hypercreative Parker sacrificed himself, fully conscious, on the rocks of prejudice and cultural ignorance; while Gillespie, heeding that awful warning, waited until he reached the shores of economic and creative security before even obliquely criticizing American society. Mingus (five years younger than Dizzy, less than two years younger than Bird) was temperamentally drawn to follow both directions."

Nearby is Carl Van Vechen’s, Dizzy Gillespie, 1955, Hand Gravure from original 35mm negative, 22”x14”. Van Vechen, a white man intrigued with Harlem life, crafted, “Nigger Heaven”, a novel in which he had recklessly written,“Nigger Heaven! That’s what Harlem is. We sit in our places in the gallery of this New York theatre and watch the white world sitting down below in the good seats in the orchestra. Occasionally they turn their faces up towards us, their hard, cruel faces, to laugh or sneer, but they never beckon.” The past holds a strong grasp through this show. There's also his sophisticated, Ella Fitzgerald, 1940, Hand Gravure from original 35 mm negative, 22" x 14", and Bessie Smith, 1936, Hand Gravure from original 35 mm negative, tugging the viewer back to the life some used to live.

There’s much, much more to be seen and felt. There’s the photography and dreamy fluid work of Ming Smith, and her life experiences hanging there. Smith's photographic careful use of half tones notations of life as she travels through revealing and responding to her personal engagement…and in this place. “It was part of my world”, she states, capturing, George Coleman in Loft Scene 80’s, Print, 14 3/8 x 11 ¼ framed, and her, Love of Duke Ellington in Steel Mill Town, August Wilson’s Hill District, 1990, Print, 23 ¾ x 18” framed.

The Cooper’s, “free-to-the-public” gallery highlights contemporary art in exhibitions, and installations, as well as workshops artist talks, and symposia. Part of the Hutchins Center for African and African-Ameican Research at Harvard University, it is housed in a space designed byprominent architect David Adjaye, designer of the Museum of African American History in Washington, DC and a finalist for the design of the future Presidential Library of Barack Obama in Chicago. It provides a refreshing alternative to just muddling though found in many locales, now on life support, housing works of the African Diaspora. It's straight...no chaser.

It's a healthy look at a truly American genre, and a wiff of nostalgia might make a call for the people and places that are no longer part of who one is, but what one will realize. It’s still way a part of in an opening, to do so, if there’s an urge to get in touch with the music, do it.

With this show, the Gallery continues to fulfill its mission, and by coincidence, opens in the 50 anniversary year of the Verve Records label, a house that early on worked with the likes of Charlie Parker, Bill Evans, Billie Holiday, Oscar Peterson, Ben Webster and many, many others.

The Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art is located at 102 Mount Auburn St., Cambridge, MA 02138. "Art of Jazz:Form/Performance/Notes" runs February 3 through May 8, 2016

Jeffrey McNary is a cambridge, MA based writer. His work can be found in Chicago Art Magzine, Chicago Art Review, Iconoclast, New City, Transition Magazine, and other outlets. He is currently crafting a work for stage which explores the friendship between American authors James Baldwin and William Styron.

jeffrey mcnary

e-mail:

jeffmvy@netscape.net

e-mail:

jeffmvy@netscape.net